In 1758 a man named Carolus Linnaeus (Carl von Linne) developed a classification system for all animals. He divided the animal Kingdom into groups that each had things in common. Then he divided those groups into smaller groups that had even more things in common. When he finally finished, there were seven levels in his system. At the lowest level is the species. His scientific classification system is still used today.

These seven levels are shown below. Here is how scientists classify an American Robin:

| Level | Name | Description |

| Kingdom | Animalia | Animals |

| Phylum | Chordata | Animals with backbones |

| Class | Aves | Animals called Birds |

| Order | Passeriformes | Birds that perch |

| Family | Turdidae | All Thrushes |

| Genus | Turdus | Similar Thrushes |

| Species | Turdus migratorius | American Robin |

Notice that the species has two names. The names are in Latin. The first name is the Genus and the second is another name that often describes a prominent feature of the bird. The second name may also be a person’s name — often the name of the ornithologist that first discovered the bird.

Scientists sometimes will talk about “races” or “tribes” of one species. Human Beings are a species but there are many races of humans. (Think of a Japanese Sumo wrestler, an pygmy from New Guinea and a Masi warrier from Africa). The same is true for birds. When you go birding you may notice that some birds, such as the Yellow-rumped Warbler, look different in the East than the same species does in the West. Different races of the same species often are separated geographically.

Birds are Animals. Birds have feathers and lay eggs. All birds have wings. However, not all birds can fly. The Ostrich is too heavy to fly. Penguins use their wings to swim, instead of to fly. A few birds “forgot” how to fly because they spent all their time on the ground. After many centuries, their ancestors had evolved to the point where they were unable to fly. Often these birds live on remote islands in the Pacific Ocean. They are vulnerable to introduced animals and snakes.

As scientists learn more about birds, they are able to arrange the 10,400 species of birds into the correct Order, Family and Genus. There is a surprising amount of debate about some birds. Are they really a species or not? They may actually be a race of a similar species in the same genus. For example about twenty years ago scientists decided the Baltimore Oriole was really the same bird as the Bullock’s Oriole. The Baltimore Oriole lives in the Eastern United States and the Bullock’s Oriole lives in the Western United States. Both birds were called the Northern Oriole. In 1995 the scientists changed their minds and decided these really were two separate species! This “splitting” is becoming more frequent today as DNA research is used. For example, a bird called the Rosy Finch was recently declared to be THREE different birds!

Combining two apparent species into just one new species is called “lumping.” Separating a species into two or more species is called “splitting.” Birders like it when scientists decide to “split” a bird because then there are more species of birds to see. Their “Life List” of birds may go up because they had already seen both “races” of the old species. There seems to be a trend today toward splitting birds. This is because better methods of research are now available to examine birds at the microscopic level.

Today there are many scientists investigating birds. They work at places like The Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia or Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology or Pennsylvania State University or Louisiana State University. It is certain that their work will make bird species appear and disappear as they continue lumping and splitting. That is why a computerized list of the world’s birds makes more sense than a printed list in a book. You can update your computer and always have the best, most current classification list possible. A book listing all the birds of the world is obsolete by the time you read it.

Scientific classification is undergoing a big change. Dr. Charles G. Sibley did research for over twenty years using DNA from bird’s blood. He and his associates suggested a new way to classify the birds of the world. His system is called the Sibley/Ahlquist/Monroe classification or SAM for short. Dr. Sibley discovered that some species are more closely related than anyone thought. He also rearranged the Orders and Families in a way that is quite unexpected. Additional research being done today is proving that Dr. Sibley is probably right. The SAM classification seems, to many scientists, to be better than the one used for the last 100 years. Scientists want to be very sure this new classification is better than the traditional classification before they make an official change.

American Ornithological Society’s Annual Taxonomy Changes

Below are the supplements issued since publication of the 7th edition of the Check-list of North American Birds (American Ornithologists’ Union [AOU] 1998).

See Annual Supplements to AOC bird list

Number of Bird Species in the World:

There are over 10,550 species of birds in the world. Over 1,000 have been seen in the U.S. and Canada. About 1,000 have been seen in Europe as well. By far the largest concentration of bird species are found in South America. Over 3,300 species have been seen there. In Brazil, Colombia and Peru the species count for each country tops 1,800. Here are some very general figures for the species count for each continent:

3,500 South America

3,400 Asia

2,300 Africa

2,000 North and Central America & Caribbean

1,700 Australia and surrounding islands

1,000 Europe

100 Antarctica

Birdnet is the “umbrella” site for all U.S. ornithological societies.

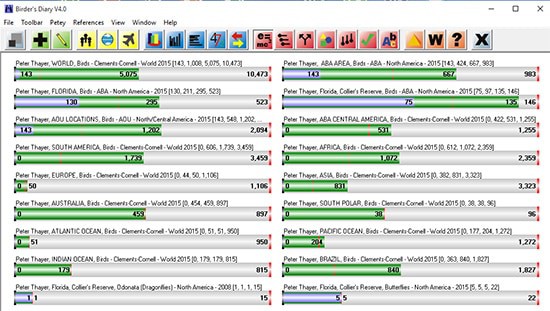

The World’s Best Listing and Recordkeeping Program for Birders

Advanced Edition: Clements/Cornell World Taxonomic List

(Many other Taxonomic lists are also available)

This program was created by Thayer Birding Software in 1994 and sold to Jeff Jones in 2005.

We highly recommend this software.